Commentary: Repoliticizing Puerto Rico on the Biggest U.S. Stage

Bad Bunny reasserted Puerto Rican identity as political, shaped by colonialism, resistance, and survival, and carried that consciousness to the Super Bowl - one of the largest stages in the world.

Moments of mass joy and cultural recognition are directly related to our political life as people of the global south. When Caribbean artists including Bad Bunny affirm their cultural and historical consciousness on a mass scale, they help create shared identity across language, memory, belonging, generations and diasporas.

This article highlights the many layers of Puerto Rican socio-political symbolism woven throughout Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime performance.

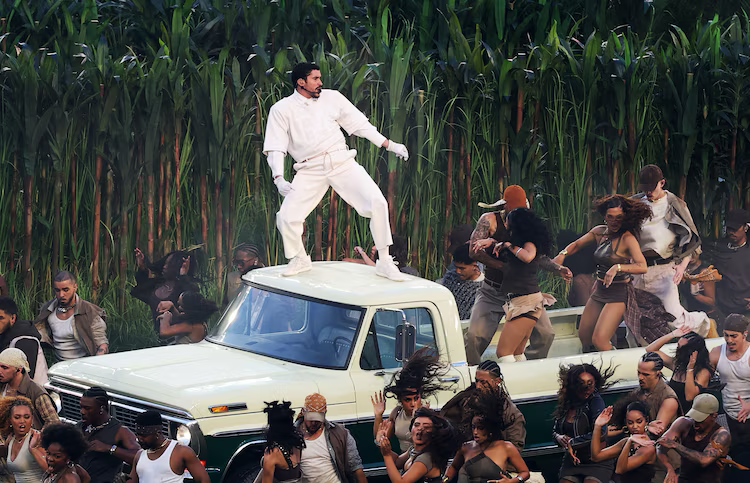

The performance opens in sugarcane fields with a campesino, a Latin American Indigenous farm laborer, dressed in white clothing and a straw hat, traditional garb of those working under the sun. This image centers Puerto Rico’s working class and agricultural roots. For much of its history, Puerto Rico was a majority agricultural economy with a huge reliance on sugar cane farming.

In 1947, Operation Bootstrap, imposed by the U.S. government, fundamentally shifted Puerto Rico’s economy from a majority agricultural one to industrial to attract U.S. corporations. U.S. companies were offered tax exemptions, land, and access to low-wage labor. While this strategy brought factories to Puerto Rico, particularly pharmaceutical and pesticide companies, it devastated local industries, especially agriculture, and increased Puerto Rico’s dependency on U.S. imports.

As rural employment disappeared, many Puerto Ricans were pushed into cities like San Juan to work in factories, while others were forced to migrate to the U.S. mainland. This migration also served to vacate land for further U.S. economic use. Pesticide companies conducted field trials across the archipelago, contaminating land and water and contributing to increased cancer rates, fertility issues, pregnancy complications, birth defects, and developmental disorders.

From this grounding, the performance transitions into scenes of daily life. Multiracial, intergenerational elders play dominoes, centering respect for elders, particularly working-class elders, and the importance of shared public space. Street vendors and cart workers pass through the frame, including a coconut seller, highlighting Puerto Rico’s relationship to land, food, and informal economies.

Women appear getting their nails done, emphasizing the value placed on beauty and Puertorriqueña femininity as part of everyday life rather than luxury. Piraguas, shaved ice with syrup sold on the street, signal working-class joy and familiar street food. Boxing, a major sport in Puerto Rican culture, appears as a marker of discipline, endurance, and pride rooted in working-class neighborhoods.

Puerto Rican musical genres including Salsa, Bomba, Plena, and Reggaetón structure the entire performance narrative.

Bomba and Plena emerged as Afro-Puerto Rican musical traditions rooted in communal rhythm, storytelling, and resistance across the archipelago. Salsa developed later through Puerto Rican and Caribbean diasporic life in New York, carrying these traditions forward into a global sound shaped by migration, labor, and collective memory.

The performance then situates Reggaetón within this longer musical continuum. Reggaetón is a genre shaped through Black Caribbean and Latin American working-class cultures, with deep roots in Panamanian music that emerged under U.S. imperialism and globalization. Black Panamanian communities adapted Jamaican reggae during the era of U.S. military control of the Panama Canal, and through migration, port cities, military routes, and diasporic networks, this sound circulated across the Caribbean and Latin America. Puerto Rico became a key site of transformation when Puerto Rican youth, DJs, and producers encountered Panamanian reggae in Spanish and reworked it locally, blending it with hip-hop, Puerto Rican Spanish, and Afro-Puerto Rican musical traditions. Through this creative exchange, Reggaetón took shape on the archipelago as a distinctly Puerto Rican expression.

The performance samples foundational Puerto Rican reggaetoneros including Tego Calderón and Don Omar, grounding the genre in Black Puerto Rican history and honoring its lineage.

Bad Bunny brings in Karol G and Cardi B, signaling Latin American and Caribbean solidarity across borders and diasporas. Cardi B’s presence acknowledges her role as a major Caribbean diasporic figure shaped by Dominican and Trinidadian heritage and by Caribbean and Puerto Rican New York.

Nueva York appears repeatedly as a central site of Puerto Rican life shaped by colonialism and forced migration. Iconic Nuyorican small businesses that have been fighting to stay open during extreme gentrification fill the performance, including bars, barbershops, food vendors, and social clubs. Tonita’s Bar (and Tonita herself!) in Williamsburg, Brooklyn is featured as a real, working-class cultural institution where music, memory, and community converge.

The iconic pink house from Bad Bunny’s album Debí Tirar Más Fotos appears as a modest but vibrant working-class home, complete with a satellite dish. It is colorful, creative, and lived-in, pointing to a celebration of ordinary life.

Family scenes recur throughout the 15 minute performance. People gather around the TV. Children fall asleep at loud family parties, a familiar joke across Puerto Rican and broader Latin culture. These moments show intergenerational life as continuous and communal. At one point, Bad Bunny hands his Grammy to a Puerto Rican child, which some interpret as representing Bad Bunny as a child.

A pickup truck appears as a practical tool of agricultural and working-class life, bringing us back to the sugarcane fields and reinforcing the connection between labor and land. A full Puerto Rican orchestra enters, led by a conductor wearing a lapel pin of the flor de maga, Puerto Rico’s national flower, reflecting common Puerto Rican reverence for nature and national identity. Lady Gaga later appears also wearing the flor de maga, signaling respect for Puerto Rican culture as she sings a Salsa version of her song.

A wedding scene follows, referencing popular Nueva York style Puerto Rican wedding traditions and reinforcing diasporic continuity. One of the most visible examples of this is Valencia Bakery, a Puerto Rican–owned bakery with locations in the Bronx and Brooklyn. Valencia Bakery was first featured in the music video for NUEVAYoL, where a custom “Benito Cake” appeared onscreen. Following the video’s release, the cake went viral, drawing widespread attention to the bakery and significantly increasing demand. That same bakery was later featured again during the Super Bowl performance, extending this moment of visibility from a music video to one of the largest televised stages in the world. By repeatedly uplifting Valencia Bakery, the performance highlights how Puerto Rican small businesses function as cultural anchors across generations and geographies.

The performance then turns explicitly political with El Apagón, addressing Puerto Rico’s ongoing electricity crisis and situating it within labor struggle and colonial extraction. The imagery of electrical workers climbing sparking electrical poles reflects daily reality under privatization, particularly following Hurricane Maria, when disaster was used as an opportunity to dismantle public infrastructure rather than repair it.

When Bad Bunny originally released El Apagón in his 2022 album Un Verano Sin Ti, he did more than drop a music video. He released a 20-plus-minute mini-documentary titled Aquí Vive Gente (“People Live Here”), directed by Puerto Rican journalist Bianca Graulau and visually tied to the song. The project blends the song’s rhythms with reporting on recurring blackouts, privatization of energy infrastructure, gentrification, and displacement across the Puerto Rican archipelago, using real footage, community voices, and investigative framing to connect the music to ongoing social and economic struggles on the ground. By choosing to pair the song with this documentary form, Bad Bunny extended the artistry beyond cultural symbolism, insisting that the issues the song names are not abstract.

At the center of this struggle is UTIER, Puerto Rico’s long-standing public-sector electrical workers’ union. UTIER has faced sustained attacks from the U.S. government precisely because it cannot be easily co-opted. As privatization expanded, UTIER workers have been pushed out of their jobs, denied benefits, and subjected to defamation campaigns. Contracts were written to weaken the union, including clauses forcing workers to join U.S.-based unions including IBEW instead.

Electric bills continue to rise, with many Puerto Ricans spending over half of their income just to maintain basic service. Meanwhile, mainland U.S. electrical workers affiliated with IBEW were brought in and paid more than local workers, despite lacking the same knowledge of the archipelago’s grid and terrain. UTIER members have faced surveillance, intimidation, and harassment, including police threats and federal interference.

By visibly including electrical workers during El Apagón, the performance places the crisis where it belongs, at the intersection of labor, privatization, and colonial control. Electricity is framed as a public necessity and the workers who maintain it are shown as essential.

The performance continues with regional solidarity. Latin American and Caribbean flags fill the stage. Puerto Rico’s light blue flag is raised, which carries a distinct political history. While the red, white, and blue flag is widely recognized today, the light blue variation has long been associated with the independence movement. Under U.S. colonial rule, expressions of Puerto Rican nationalism were actively repressed, and beginning in the late 1940s, U.S.-imposed laws criminalized the display of the light blue version of the Puerto Rican flag and other symbols of self-determination. This light blue flag came to signify resistance to U.S. control and a rejection of imposed assimilation, marking a lineage of anti-colonial struggle rather than aesthetic preference.

Caribbean nations are named and represented, including flags of the least recognized and known countries including Haiti, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago emphasizing shared history and unity. Bad Bunny also explicitly names Cuba despite its demonization by the U.S. government due to its socialist and anti-imperialist project.

The performance explicitly names Puerto Rico’s relationship to other colonized archipelagos. At one point within the performance, Ricky Martin is featured singing Bad Bunny’s Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaii, honoring Martin’s influence on Puerto Rican music and global recognition. Bad Bunny’s Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaii situates Puerto Rico within a broader history of U.S. colonial control.

A guineo, or banana, tree stands behind him as he sings, grounding the moment in land and extraction. The song draws a direct parallel between Puerto Rico and Hawaii, warning against displacement, land theft, and the slow erasure of culture under U.S. rule.

The lyrics name what colonization consists of in practice. Communities are pushed out. Elders are forced to leave. Neighborhoods are taken. Beaches and rivers are privatized. The song repeats a clear warning not to let Puerto Rico become as harmed as Hawaii, a former colony and current U.S. state where tourism, corruption, and political control hollowed out Indigenous life and local sovereignty.

The chorus insists on holding onto the flag and remembering who you are. This is a refusal to forget land, language, and community in the face of displacement.

Through this 15 minute performance, Puerto Rico is being placed within a global pattern of colonial exploitation. Bad Bunny has said that he wrote the song thinking directly about Puerto Rico and was struck by how people across Latin America and beyond recognized their own experiences in the song. That response reflects the song’s clarity.

The performance closes with the phrase “we’re still here,” echoing Indigenous survival and signaling resistance to displacement, policing, and ICE. Bad Bunny ends with his song Debí Tirar Más Fotos and closes by referring to Puerto Rico as “mi patria”, naming Puerto Rico explicitly as a country rather than a U.S. territory or “Commonwealth”.

This performance was a collage of Puerto Rican life, history, and Latin American and Caribbean solidarity. For decades, the United States has worked to depoliticize Puerto Rican identity, reducing it to culture without history, celebration without power, and representation without self-determination. Puerto Ricanness has been recast as something folkloric and entertaining, stripped of its political context and disconnected from the conditions that shaped it. This is precisely what makes the performance artistically significant. By rooting joy in historical memory, labor struggle, and cultural lineage, Bad Bunny reasserted Puerto Rican identity as political, shaped by colonialism, resistance, and survival, and carried that consciousness onto one of the largest stages in the world.